Every time we count, calculate, or type a number into our phones or laptops, we’re using symbols that feel almost as ancient as time itself: 1, 2, 3, 4… They’re called Arabic numerals today, but their story doesn’t begin in Arabia. Nor does it end there. In fact, it winds through ancient India, travels across the Islamic world, and eventually arrives in Europe, where it quietly replaces the clunky Roman numerals we now associate with monuments and clocks.

This is the story of numbers—not just as symbols, but as carriers of knowledge across civilizations.

Where it really began

The earliest evidence of a positional decimal number system—the idea that the place of a digit determines its value—comes from India. Ancient Indian mathematicians not only developed this positional system but also introduced the concept of zero as a number with its own mathematical identity. This might seem trivial to us today, but at the time, it was nothing short of revolutionary.

The oldest known inscription of the numeral “0” as a placeholder is found in the Bakhshali manuscript, a mathematical text dated by radiocarbon methods to as early as the 3rd or 4th century CE. And long before that, Indian mathematicians like Pingala (who worked on binary-like systems) and later Aryabhata and Brahmagupta explored place value, equations, and operations that were deeply reliant on this numerical framework.

Brahmagupta, in particular, formalized rules for zero and negative numbers—ideas that would go on to influence generations of mathematicians.

Image: Hindu astronomer, 19th-century illustration. CC-BY-ND.

How the knowledge traveled

The number system, along with broader Indian mathematical knowledge, spread to the Islamic world sometime around the 7th to 9th centuries CE. Scholars in Persia and the Arab world translated Sanskrit texts into Arabic, absorbed their ideas, and extended them further.

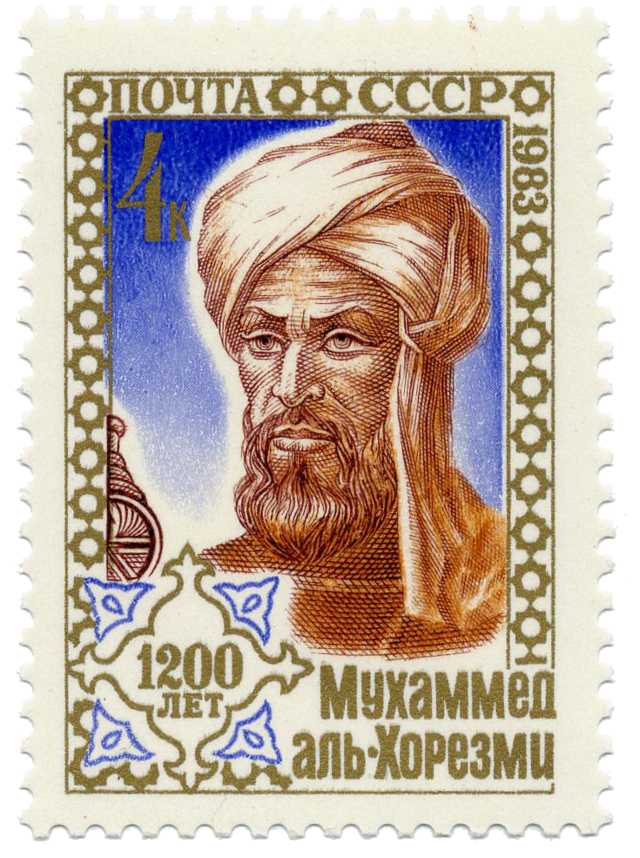

One such scholar was the Persian mathematician Al-Khwarizmi, who is often called the “father of algebra.” His treatises introduced the Indian system of numerals to the Arabic-speaking world. In fact, the Latin word “algorithm” comes from his name, and his writings became the main channel through which Indian mathematics entered Europe.

Image: Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Ḵwārizmī. (He is on a Soviet Union commemorative stamp, issued September 6, 1983. The stamp bears his name and says “1200 years”, referring to the approximate anniversary of his birth). Source: Wikimedia Commons

When these ideas were translated into Latin in medieval Spain—particularly in cities like Toledo, where Christian, Muslim, and Jewish scholars collaborated—they began influencing European mathematics. By the 12th century, the numerals had been introduced to the West as the “Modus Indorum“—the Indian method. This system was introduced to Europe by Leonardo Pisano, also known as Fibonacci, in his book Liber Abaci (1202). Fibonacci himself credited the system to the “Indians,” highlighting its superiority over the Roman numeral system then in use.

Image: Monument of Leonardo da Pisa (Fibonacci), by Giovanni Paganucci, completed in 1863, in the Camposanto di Pisa, Pisa, Italy. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Why we call them Arabic numerals

Given this journey, why are they called Arabic numerals? The answer is simple: Europeans learned them through Arabic texts. To them, the knowledge had come from the Arab world—even if it had deeper roots in India. It’s a reminder that the names we give to ideas often reflect where we encounter them, not necessarily where they were born.

It’s also a reminder of something deeper: the way knowledge flows across time and geography. It does not always come with citations or acknowledgments. What survives is the idea, not the backstory.

The quiet revolution over Roman numerals

The so-called “Hindu-Arabic” numerals slowly replaced Roman numerals in Europe. The transition wasn’t immediate—resistance to change, especially in something as fundamental as arithmetic, was strong. Roman numerals, while elegant in stone carvings, were unwieldy for calculations. Try multiplying LXIV by XXIII without converting them first.

In contrast, the Indian system—with its zero, place value, and compact notation—was built for mathematics. Over time, merchants, accountants, and scientists realized its efficiency. By the time of the Renaissance, this “foreign” number system had become the foundation of modern mathematics in Europe.

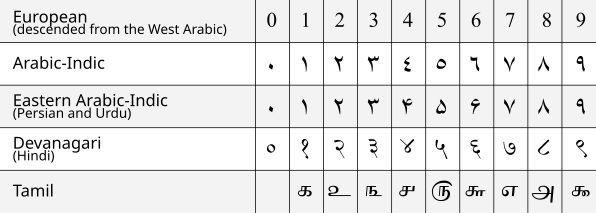

Image: Comparison between five different styles of writing Arabic numerals. The terms (“European”, “Arabic-Indic”, etc.) are written in Arial Unicode MS and still are changeable. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

A quiet lesson about knowledge

This history of numbers is simply a story—a reminder of how knowledge has always been global. Ideas are born, shaped, transmitted, forgotten, revived. Borders don’t hold them. Languages don’t confine them. The numerals we use today are not Indian or Arabic or Western—they’re human.

What we often lose, though, are the stories. As knowledge becomes embedded into daily life, its origins fade. But perhaps it’s worth pausing every now and then—not just to marvel at how far we’ve come, but to acknowledge the many quiet contributors whose names don’t make it into the textbooks.

So the next time you type a “0” or balance a spreadsheet, remember: that little circle carries a long and winding history—one that connects forests in ancient India to the libraries of Baghdad, and the towers of medieval Europe to the circuits in your device.

The Guradian has done an excellent job capturing the larger history. Check here.

Leave a Reply